Han Zheng, formerly China’s top-ranked vice-premier, has been appointed the country’s vice-president, giving the 68-year-old a role on the political stage following his retirement from the Communist Party’s Politburo Standing Committee in October.

Han’s appointment was passed by a unanimous 2,952 votes from the national legislature on Friday.

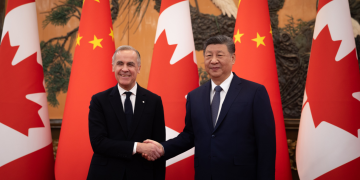

Analysts said the vice-presidency would remain a nominal role, with Han’s duties, like those of predecessor Wang Qishan, likely to be confined to representing the country at ceremonies and events overseas and receiving foreign guests in China.

“When there are foreign events that Xi [Jinping] does not like to attend himself, the vice-president can be his envoy,” said Alfred Wu, an associate professor at the National University of Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy.

“It was just like when Wang Qishan attended the queen’s funeral last year.”

Han was the only outgoing member of the powerful Politburo Standing Committee elected as a deputy to the new National People’s Congress – China’s top legislature – making him an obvious candidate to succeed Wang, 74, who followed a similar path to the vice-presidency five years ago.

President Xi and his predecessor, Hu Jintao, served as vice-president before becoming the country’s leader, but the post served as a training ground for the presidency back then.

Xi, who is beginning his third term as president at this month’s two sessions – the annual meeting of the NPC and the country’s top political advisory body – has yet to name an heir apparent.

The duties of China’s vice-president are vague. According to China’s constitution, the vice-president is supposed to “assist the president in his work” and “exercise such functions and powers of the president as the president may entrust to him”.

At the opening ceremony of the Boao Forum for Asia in 2021, Wang half-jokingly said he was not a speaker at the event, but only a temporary host ushering in Xi as the keynote speaker.

Some observers had considered Liu He, another outgoing vice-premier, as a possible vice-presidential option, given his ample experience in negotiating with Western counterparts. But, unlike Wang, he was not a member of the Politburo Standing Committee, and the post of vice-president, which carries the rank of a state leader, would have been a giant leap.

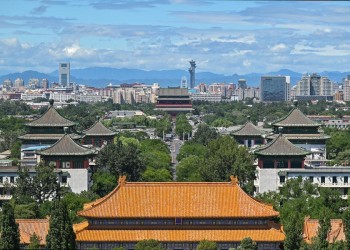

Han has spent most of his political career in Shanghai.

He headed the Communist Youth League in the municipality in the early 1990s and then gradually moved up the local government ladder. He became a vice-mayor in 1998 and mayor in 2003, remaining in that post for nine years.

As the second most important official in the municipality, Han was top aide to three Shanghai party bosses, beginning with Chen Liangyu from 2003 to 2006. When Chen, a close ally of former president Jiang Zemin, was arrested on corruption charges in 2006, Han survived and served as acting Shanghai party secretary for five months before Xi, then party boss of Zhejiang province, was given the job.

Han was an aide to Xi for five months, before Xi was promoted to the Politburo Standing Committee in 2007 and the vice-presidency in 2008.

Yu Zhengsheng succeeded Xi in Shanghai, and Han worked for him for five years before becoming Shanghai party boss himself in 2012.

Han was Shanghai’s party secretary for five years before being promoted to the Politburo Standing Committee in 2017 and executive vice-premier the next year.

Apart from being a political survivor who worked with different bosses without being seen as a challenger, the time Han spent managing cosmopolitan Shanghai gave him plenty of experience in handling foreign diplomats and investors.

“He had international experience in Shanghai and he has a good image,” Wu said.

During his five years as executive vice-premier, foreign affairs was a key focus, and Yu Tao, a senior lecturer in Chinese studies at the University of Western Australia, said that experience was an important credential when vice-presidential candidates were being weighed up.

“Han Zheng has accumulated considerable diplomatic experience since his promotion to the Politburo’s Standing Committee in 2017,” he said.

“In particular, as leader of the steering group for the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics, he coordinated, on the national level, many areas to push forward the preparation work for the 2022 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games, including associated diplomatic issues,” Yu said.

“He also served as President Xi Jinping’s special envoy to attend the opening ceremony of the Pyeongchang Winter Olympics.”

Han’s role as leader of the Belt and Road Construction Leadership Group, the State Council’s coordination body to promote the Belt and Road Initiative, also gave him experience in handling geopolitical affairs, Yu said.

“This experience could be valuable in helping him navigate China’s relationships with other countries in the office of vice-president, which includes overseeing China’s foreign policy,” he said.

In 2018, Han also became leader of the Central Coordination Group on Hong Kong and Macau Affairs, which was later upgraded to the Central Leading Group on Hong Kong and Macau Affairs.

With climate talks having become a new front of diplomacy for China and the West in recent years, Han has chaired international forums in China on energy transitions and low-carbon development, and received US climate envoy John Kerry when he visited China in 2021.

China’s next executive vice-premier is expected to be Ding Xuexiang, Xi’s chief of staff for the past five years. Ding was promoted to membership of the Politburo Standing Committee at the party’s national congress in October.